Stimulants & Oxidative Stress

Exploring how stimulants contribute to oxidative stress, its effects on cellular health, and how targeted interventions can mitigate the damage.

May 12, 2025

What is Cortisol and Why Does It Matter?

This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice. Please consult a healthcare professional for any health concerns.

Think of your brain as a bustling factory. When everything is running smoothly, the machines (your neurons) work efficiently, producing energy and maintaining essential operations like thinking, learning, and memory. But just like any factory, production creates waste—analogous to the reactive oxygen species (ROS) in your brain. Normally, there’s a cleaning crew (antioxidants) that clears the waste and keeps the factory running without a hitch. However, if the factory speeds up production—due to stress, pollution, or stimulant use—the waste can pile up faster than the crew can handle, causing damage to the equipment. Supporting the cleaning crew with proper nutrition, stress management, and healthy habits helps maintain a clean, efficient factory.

Under normal conditions, the brain tightly regulates dopamine levels to maintain proper neuronal function. The dopamine transporter (DAT) clears dopamine from the synapse and returns it to neurons, where it is either stored for future use or broken down by enzymes like monoamine oxidase (MAO) and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT). Autoreceptors detect high dopamine levels and signal neurons to adjust release. These systems work together to maintain balance and support brain health. 19

Stimulants, both prescription and non-prescription, increase dopamine by enhancing its release and blocking its reuptake via DAT, leading to elevated dopamine in the synapse.13 Excess dopamine can react with oxygen, producing reactive oxygen species (ROS), which contribute to oxidative stress. While the body has an antioxidant system to neutralize ROS, factors like pollution, UV exposure, smoking, and stimulant use can overwhelm it. The brain is particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress due to its high oxygen demand and polyunsaturated fat content, which may impact cognitive function and memory. 12,13,18

How Oxidative Stress Affects the Brain

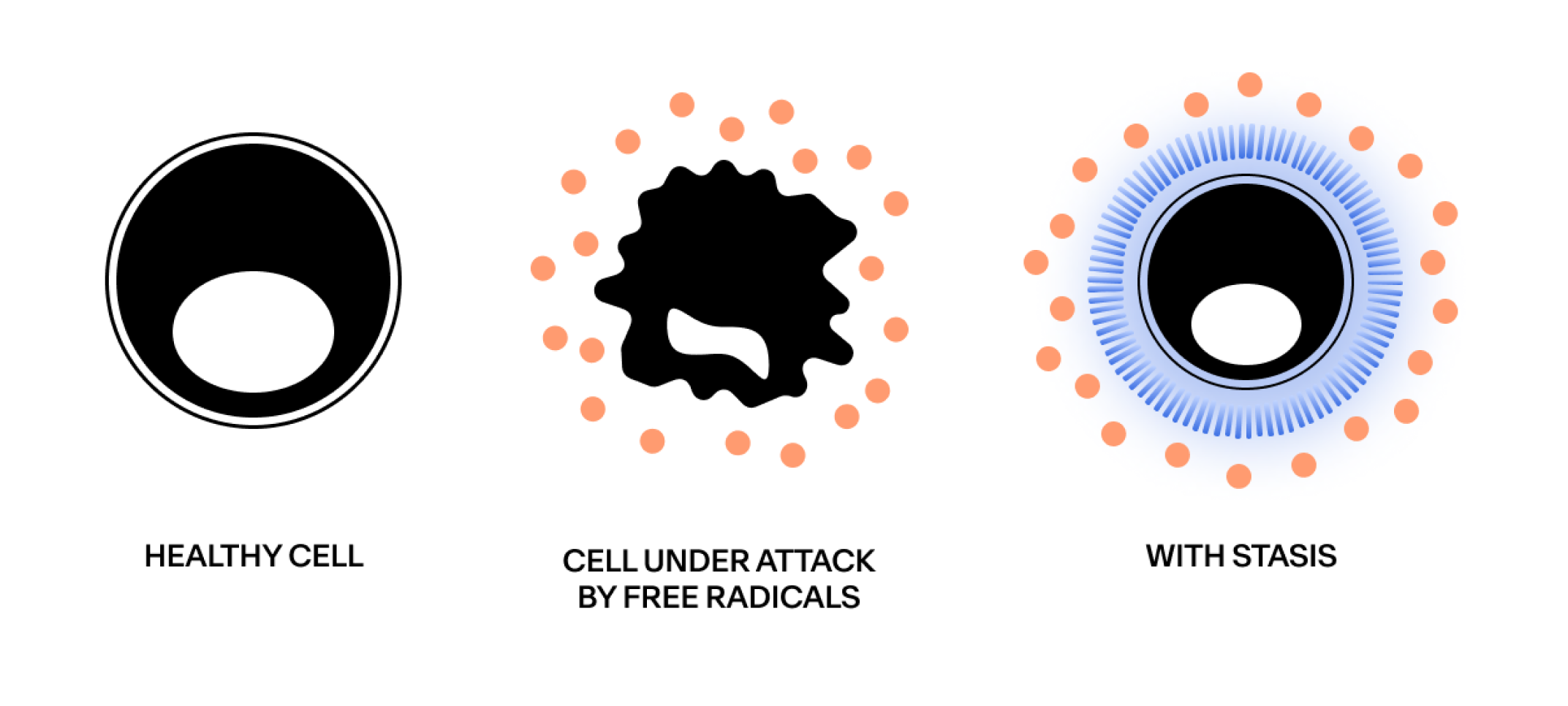

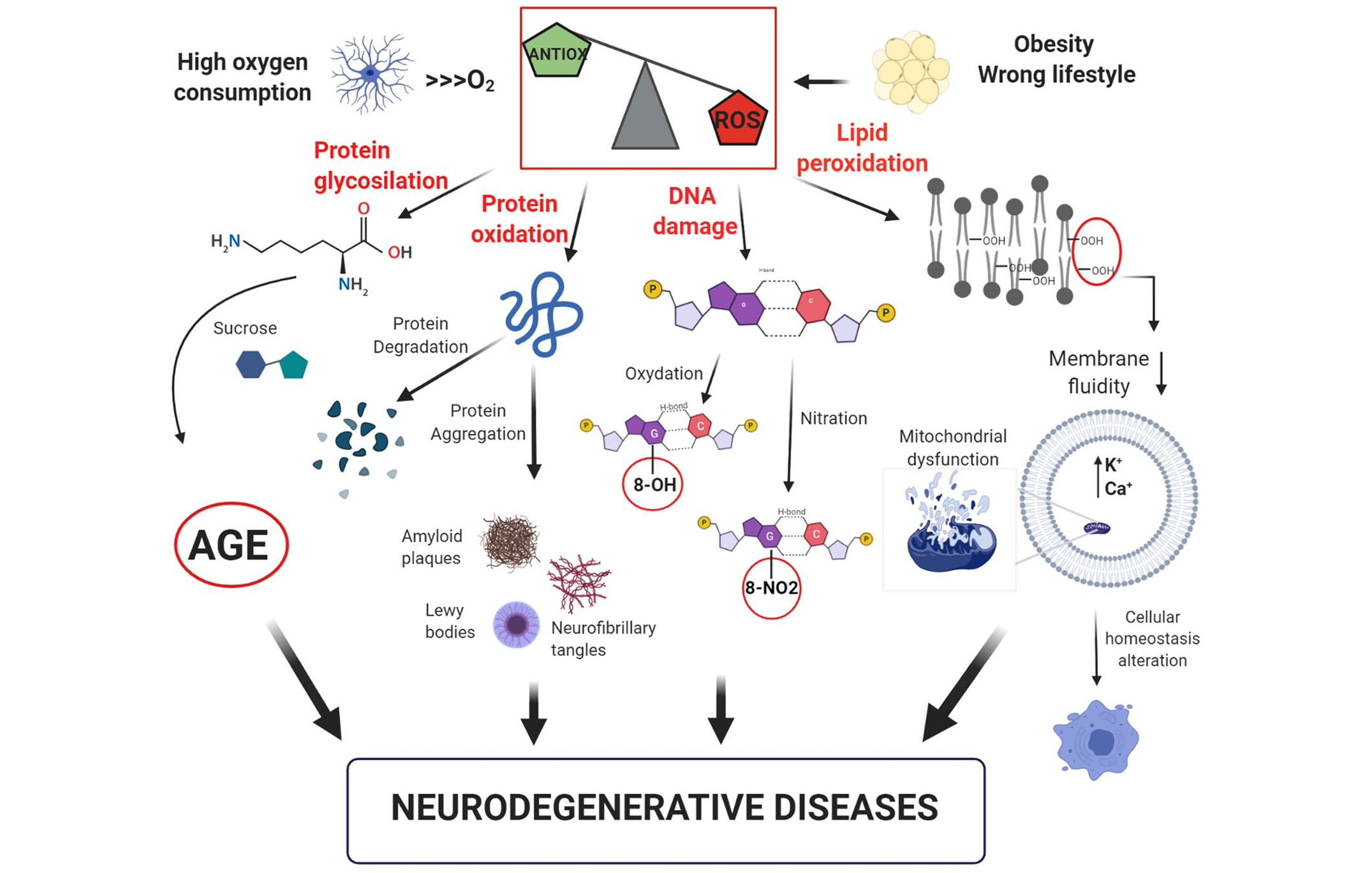

As mentioned above, oxidative stress occurs when the body has an imbalance between free radicals (reactive oxygen species, or ROS) and antioxidants. This imbalance has been studied for its impact on brain health, including the following areas:

Lipid Peroxidation

Free radicals can interact with cell membrane lipids, altering their structure and function. These changes affect the stability and permeability of cell membranes, which are critical for proper cell signaling and protection. 11

Protein Oxidation

Oxidative stress can interfere with proteins, changing their structure and function. In some cases, this may result in the formation of clumps or aggregates, which are associated with aging and challenges in maintaining cellular health. 11

DNA Integrity

ROS can interact with DNA, leading to potential changes or breaks in its structure. This has been associated with disruptions in normal cell function and health. 11

Figure 1. Model of free-radical formation and its consequences at a cellular level. 11

Mitochondrial Function

Mitochondria, often called the energy powerhouses of cells, are particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress. Prolonged exposure to ROS may reduce their efficiency, affecting energy production and contributing to challenges in cellular health and function.11,30

Supporting Brain Health & Combating Oxidative Stress

1. Stimulant Management

For individuals using stimulants, working with a healthcare professional to manage their use may be beneficial:

Proper Dosing

Taking the minimum effective dose, as guided by a healthcare provider, can help promote balanced dopamine levels and maintain optimal brain health.14,34

Regular Monitoring

Regular medical evaluations can help detect early signs of oxidative stress and adjust treatment as necessary.4,14

2. Lifestyle Factors

Incorporating healthy habits helps support the body’s natural defenses against oxidative stress:

Healthy Diet

A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats provides nutrients that support antioxidant defenses and overall brain health.11

Physical Activity

Exercise can boost antioxidant levels and improve mitochondrial function.32

Adequate Sleep

Quality sleep is essential for cellular repair and maintaining a healthy balance of oxidative and antioxidant activity.3

3. Antioxidants

The body has natural antioxidant systems, and certain nutrients help support these processes:

Endogenous Antioxidants

The body produces enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, and glutathione peroxidase, which neutralize free radicals.8

Dietary Antioxidants

Consuming foods rich in antioxidants (e.g., vitamins C and E) can help reduce oxidative stress.33

Powerful Antioxidants in Stasis Combat Oxidative Stress

Please note that Stasis is a dietary supplement. It is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease

Astaxanthin

Astaxanthin is a powerful carotenoid antioxidant derived from microalgae, recognized for its neuroprotective properties and role in supporting skin health.10,17 It has the unique ability to cross both the blood-brain barrier and cellular membranes, enabling it to neutralize free radicals and mitigate oxidative stress in both lipophilic and hydrophilic environments.1,15 Through its potent antioxidant activity, Astaxanthin has been shown to enhance mitochondrial function, protect cellular structures from UV-induced oxidative damage.1,27 Additionally, it supports brain health by helping to manage oxidative stress and maintain a balanced inflammation response.10,15

Selenium

Selenium is an essential trace mineral with antioxidant properties, crucial for immune function and thyroid hormone metabolism.26 It contributes to health by supporting the body's natural defenses against harmful compounds and by being incorporated into selenoproteins, such as glutathione peroxidase, which help maintain cellular resilience.22 Selenium’s involvement in managing oxidative stress and supporting a balanced inflammatory response highlights its importance in overall health.11,16,35

TetraSOD®

TetraSOD® is a unique ingredient that supports your body’s natural antioxidant defenses, including enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and catalase (CAT). SOD is our body’s main defense against oxidative stress and is one of the enzymes in our body belonging to the primary antioxidant system. This system is much more effective than classic antioxidants, such as carotenoids, flavonoids, or vitamins (A, E, C), as it is capable of neutralizing up to 1 million free radicals. Additionally, TetraSOD® can aid in recovery after high-intensity workouts like cross-training and endurance.29

Key Study Summaries

The following information is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice. These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This information is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease, nor is it intended to promote any specific product.

Oxidative Stress in Prolonged Methamphetamine Use

A study by Solhi et al. (2014) examined oxidative stress markers in 30 individuals with prolonged methamphetamine use compared to 30 healthy controls. The researchers observed elevated levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), a marker of lipid peroxidation, and lower total antioxidant capacity in methamphetamine users. These findings suggest a potential link between chronic methamphetamine use and oxidative changes in the body.31

Oxidative Stress After Recent Abstinence

Huang et al. (2013) evaluated oxidative stress in 44 individuals who had ceased methamphetamine use for less than 30 days, compared with 48 healthy controls. The study identified higher levels of oxidative stress markers, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and MDA, alongside lower antioxidant enzyme activity in the methamphetamine users. These observations indicate oxidative stress can persist even after recent cessation.14

Antioxidant Levels in Chronic Methamphetamine Users

Mirecki et al. (2004) analyzed brain tissue from 16 individuals with chronic methamphetamine use and 15 healthy controls, focusing on antioxidant levels. The study found reduced levels of glutathione, a key antioxidant, in the brains of chronic methamphetamine users, reflecting increased vulnerability to oxidative stress.24

Mechanisms of Oxidative Stress in Amphetamine Use

Yamamoto and Raudensky (2008) reviewed the mechanisms associated with oxidative stress induced by amphetamine-related drugs. The researchers reported that these drugs may increase ROS production, disrupt mitochondrial function, and affect cellular energy reserves. These processes were associated with metabolic changes and inflammation in neuronal systems.36

-

Citations:

- Ambati, R. R., Phang, S. M., Ravi, S., & Aswathanarayana, R. G. (2014). Astaxanthin: Sources, extraction, stability, biological activities, and its commercial applications—a review. Marine Drugs, 12(1), 128–152. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12010128

- Aseervatham, G. S. B., Sivasudha, T., Jeyadevi, R., Ananth, D. A., Kumaresan, K., & Ravikumar, S. (2013). Environmental factors and unhealthy lifestyle influence oxidative stress in humans—an overview. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 20(7), 4356-4369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-013-1748-0

- Atrooz, F., & Salim, S. (2020). Sleep deprivation, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology, 119, 309-336. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.apcsb.2019.03.001

- Azzi, A. (2022). Oxidative stress: What is it? Can it be measured? Where is it located? Can it be good or bad? Can it be prevented? Can it be cured? Antioxidants, 11(8), 1431. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11081431

- Balic, I., Obradović, D., & Tomašević, M. (2018). Superoxide dismutase-derived products: Extramel® and their impact on oxidative stress biomarkers. Antioxidants, 7(4), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox7040055

- Belviranlı, M., & Okudan, N. (2021). Melon-derived superoxide dismutase (Extramel®) improves cognitive performance and reduces oxidative stress in older adults. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 16, 1355–1363. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S326598

- Carillon, J., Rouanet, J. M., Cristol, J. P., & Brion, R. (2013). Superoxide dismutase administration, a potential therapy against oxidative stress-related diseases: Several routes of supplementation and proposal of an original mechanism of action. Pharmaceutical Research, 30(11), 2718–2728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-013-1113-5

- Carvalho, F., Fernandes, E., Remião, F., Gomes-Da-Silva, J., Tavares, M. A., & Bastos, M. D. (2001). Adaptive response of antioxidant enzymes in different areas of rat brain after repeated d-amphetamine administration. Addiction Biology, 6(3), 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556210120056544

- Cristol, J. P., Carillon, J., & Brion, R. (2014). Extramel® supplementation reduces stress, fatigue, and oxidative stress in humans: A randomized, placebo-controlled study. Nutrients, 6(6), 2348–2359. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6062348

- Fassett, R. G., & Coombes, J. S. (2011). Astaxanthin: A potential therapeutic agent in cardiovascular disease. Marine Drugs, 9(3), 447–465. https://doi.org/10.3390/md9030447

- Franzoni, F., Scarfò, G., Guidotti, S., Fusi, J., Asomov, M., & Pruneti, C. (2021). Oxidative stress and cognitive decline: The neuroprotective role of natural antioxidants. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2021.729757

- Friedman, J. (2010). Why is the nervous system vulnerable to oxidative stress? Oxidative Stress and Free Radical Damage in Neurology, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60327-514-9_2

- Govitrapong, P., Boontem, P., Kooncumchoo, P., Pinweha, S., Srisurapanont, M., & Kotchabhakdi, N. (2010). Increased blood oxidative stress in amphetamine users. Addiction Biology, 15(1), 100-102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00176.x

- Greenhill, L. L., Pliszka, S., & Dulcan, M. K. (2002). Practice parameter for the use of stimulant medications in the treatment of children, adolescents, and adults. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(2 Supplement), 26S-49S. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200202001-00003

- Guerin, M., Huntley, M. E., & Olaizola, M. (2003). Haematococcus astaxanthin: Applications for human health and nutrition. Trends in Biotechnology, 21(5), 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-7799(03)00078-7

- Hariharan, S., & Dharmaraj, S. (2020). Selenium and selenoproteins: Its role in regulation of inflammation. Inflammopharmacology, 28, 667–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-020-00690-x

- Higuera-Ciapara, I., Félix-Valenzuela, L., & Goycoolea, F. M. (2006). Astaxanthin: A review of its chemistry and applications. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 46(2), 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408690590957188

- Huang, M., Lin, S., Chen, C., Pan, C., Lee, C., & Liu, H. (2013). Oxidative stress status in recently abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 67(2), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12025

- Juárez Olguín, H., Calderón Guzmán, D., Hernández García, E., & Barragán Mejía, G. (2016). The role of dopamine and its dysfunction as a consequence of oxidative stress. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2016, Article 9730467. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9730467

- Kooncumchoo, P., Sharma, S., Porter, J., Govitrapong, P., & Ebadi, M. (2006). Coenzyme Q10 provides neuroprotection in iron-induced apoptosis in dopaminergic neurons. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience, 28(2), 125-141. https://doi.org/10.1385/JMN:28:2:125

- Liu, F., Huang, J., Hei, G., et al. (2020). Effects of sulforaphane on cognitive function in patients with frontal brain damage: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMJ Open, 10, e037543. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037543

- Lu, J., & Holmgren, A. (2009). Selenoproteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 284(2), 723–727. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.R800045200

- Mead, A., Delibaş, B., Önger, M. E., & Kaplan, S. (2024). The potential positive effects of coenzyme Q10 on the regeneration of peripheral nerve injury. Exploration of Neuroprotective Therapy, 4, 288–299. https://doi.org/10.37349/ent.2024.00083

- Mirecki, Anna et al. “Brain antioxidant systems in human methamphetamine users.” Journal of neurochemistry vol. 89,6 (2004): 1396-408. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02434.x

- Nouchi, R., Hu, Q., Ushida, Y., Suganuma, H., & Kawashima, R. (2022). Effects of sulforaphane intake on processing speed and negative moods in healthy older adults: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.929628

- Office of Dietary Supplements. (2024). Selenium: Fact sheet for health professionals. National Institutes of Health. Accessed January 6, 2025. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Selenium-HealthProfessional/

- Pashkow, F. J., Watumull, D. G., & Campbell, C. L. (2008). Astaxanthin: A novel potential treatment for oxidative stress and inflammation in cardiovascular disease. American Journal of Cardiology, 101(10A), 58D–68D. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.02.010

- Shah, A., Varma, M., & Bhandari, R. (2024). Exploring sulforaphane as neurotherapeutic: Targeting Nrf2-Keap & NF-kB pathway crosstalk in ASD. Metabolic Brain Disease, 39(2), 373–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-023-01224-4

- Sharp, M., Sahin, K., Stefan, M., Orhan, C., Gheith, R., Reber, D., Sahin, N., Tuzcu, M., Lowery, R., Durkee, S., & Wilson, J. (2020). Phytoplankton Supplementation Lowers Muscle Damage and Sustains Performance across Repeated Exercise Bouts in Humans and Improves Antioxidant Capacity in a Mechanistic Animal. Nutrients, 12(7), 1990. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12071990

- Shin, E. J., Tran, H. Q., Nguyen, P. T., Jeong, J. H., Nah, S. Y., Jang, C. G., Nabeshima, T., & Kim, H. C. (2018). Role of mitochondria in methamphetamine-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity: Involvement in oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and pro-apoptosis—a review. Neurochemical Research, 43(1), 66-78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-017-2318-5

- Solhi, Hassan et al. “Oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation in prolonged users of methamphetamine.” Drug metabolism letters vol. 7,2 (2014): 79-82. doi:10.2174/187231280702140520191324

- Sorriento, D., Di Vaia, E., & Iaccarino, G. (2021). Physical exercise: A novel tool to protect mitochondrial health. Frontiers in Physiology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.660068

- Sun, H., Wang, D., Ren, J., Chen, L., Feng, X., Zhang, M., Xu, L., & Tang, R. (2023). Vitamin D ameliorates Aeromonas hydrophila-induced iron-dependent oxidative damage of grass carp splenic macrophages by manipulating Nrf2-mediated antioxidant pathway. Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 142, Article 109145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsi.2023.109145

- Tucker, J. E. (2021). Prescription stimulant-induced neurotoxicity: Mechanisms, outcomes, and relevance to ADHD. Michigan Journal of Medicine, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.3998/mjm.1437

- Ventura, M., Melo, M., & Carrilho, F. (2018). Selenium and thyroid function. Molecular and Integrative Toxicology, 157–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95390-8_8

- Yamamoto, B.K., Raudensky, J. The Role of Oxidative Stress, Metabolic Compromise, and Inflammation in Neuronal Injury Produced by Amphetamine-Related Drugs of Abuse. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 3, 203–217 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11481-008-9121-7

- Young, A. J., Johnson, S., Steffens, D. C., & Doraiswamy, P. M. (2007). Coenzyme Q10: A review of its promise as a neuroprotectant. CNS Spectrums, 12(1), 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852900020538

- Zhang, Y., Talalay, P., Cho, C. G., & Posner, G. H. (1992). A major inducer of anticarcinogenic protective enzymes from broccoli: Isolation and elucidation of structure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 89(6), 2399–2403. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.89.6.2399